The Quiet War Between Abstraction and Detail

Preserving the right knowledge in a world that demands constant learning

Every time you walk into a new restaurant, your brain solves an invisible problem: Which parts of this experience are specific to this place (the menu, the layout, the staff) and which parts are general rules you can transfer (how to order, where to sit, when to pay)? Extract too much shared structure and you’ll confidently walk to the wrong counter. Protect too many specific details and you’ll fumble through every new restaurant like it’s your first.

This balance, between learning patterns that transfer and preserving details that matter, appears fundamental to how we navigate a world where some things repeat (traffic patterns, social norms, the physics of thrown objects) and some things are unique (this particular intersection floods, this friend needs space when upset, this specific mushroom will kill you).

The capacity for structural learning, extracting regularities that apply across situations, may be one of the defining features of human cognition. When a child learns that adding “ed” creates past tense, they’ve discovered a rule that applies to thousands of verbs they’ve never encountered. When you recognize that a new coworker uses the same conflict-avoidant communication style as your sibling, you’ve extracted a pattern that predicts future interactions. The alternative, learning every situation as a unique instance requiring its own solution, would be computationally intractable.

But structural learning creates a fundamental tension. The same cognitive machinery that lets you rapidly transfer knowledge to new situations may overwrite what you learned before. Learn French after Spanish and you might start mixing verb conjugations. Update your mental model of how your boss communicates and you might misremember what they actually said last month. The brain must somehow balance the benefits of generalization against the risk of interference.

A Task That Makes Strategies Visible

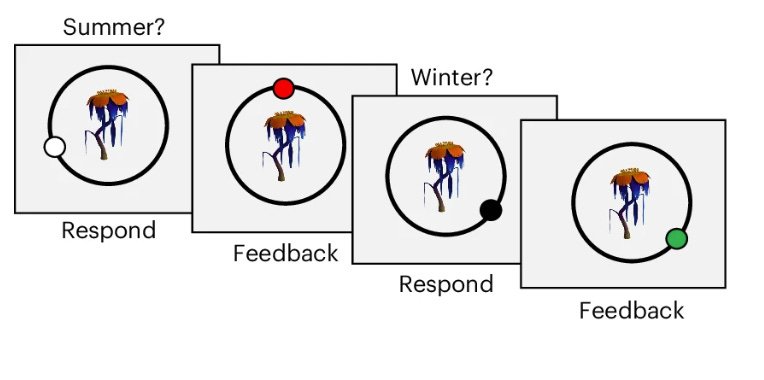

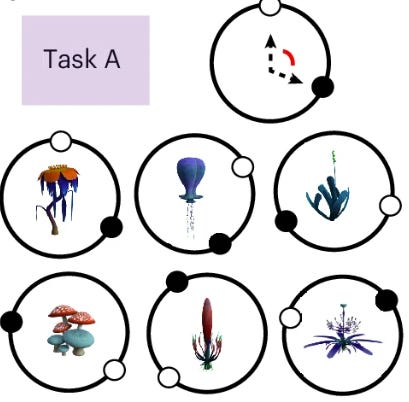

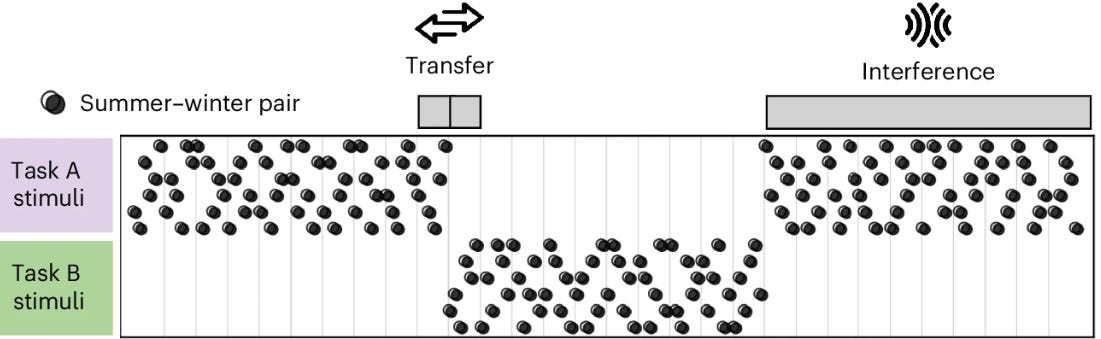

A new paper in Nature Human Behaviour by Eleanor Holton, Chris Summerfield, and colleagues has developed an elegant way to observe these competing strategies in action. The design is deceptively simple: participants learned to map fictional plants to locations on a circular planet, with separate locations for summer and winter. The key structural feature is that within each set of plants, there was a consistent angular rule. Winter locations were always a fixed offset from summer locations (say, 120 degrees clockwise).

Participants first learned one set of six plants (Task A) over ten repetitions.

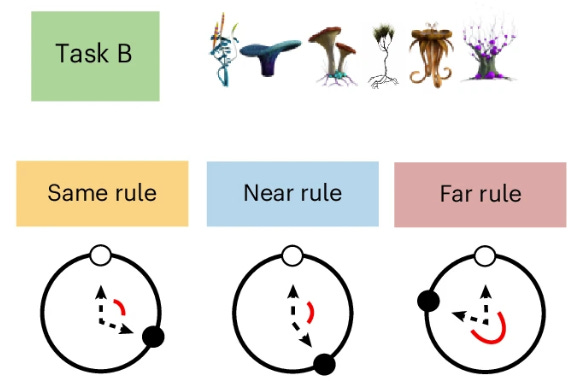

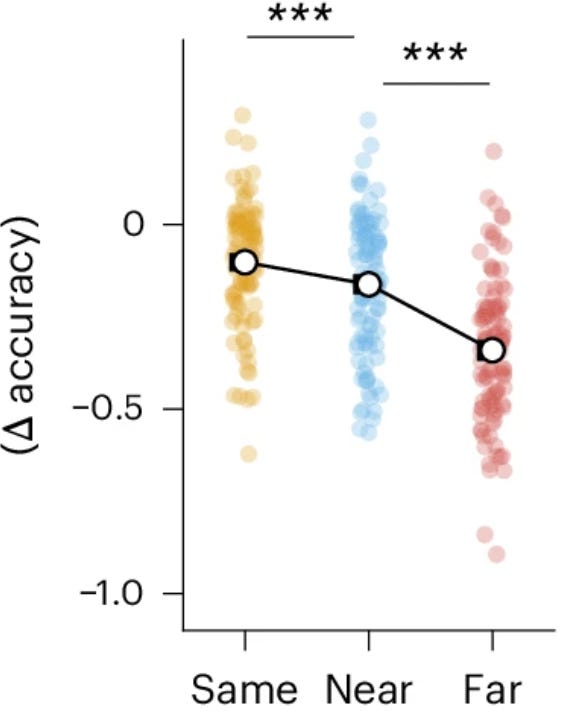

Then they encountered six entirely new plants (Task B) with their own summer-winter rule, either identical to Task A, shifted by 30 degrees, or rotated 180 degrees.

After learning Task B, they returned to the original Task A plants, but this time received feedback only for summer locations. This allowed the team to observe what rule participants spontaneously applied when retested.

The experimental design cleverly separates two phenomena that usually travel together. Transfer refers to how much knowledge of rule A accelerates learning of rule B. If you immediately apply the 120-degree rule to new plants, your initial performance on Task B should be good (when the rule is similar) or systematically biased (when the rule differs). Interference refers to whether learning rule B corrupts your memory of rule A. When retested on the original plants, do you still apply rule A correctly, or do you now mistakenly use rule B?

In most learning paradigms, these processes are confounded. Here, the structure makes different algorithmic strategies visible through their distinct signatures across transfer and interference conditions.

Heterogeneity Hidden Beneath Averaged Performance

There are many interesting things about this paper (and some things that require taking with a grain of salt that I will point out in due course), but one big takeaway is how well individual differences in strategy choice was revealed by this work.

If you average across all participants (which many people routinely do), behavior would almost certainly appear to be relatively uniform. This is because people learn both tasks to high accuracy. Mean performance in Task B appears similar across individuals.

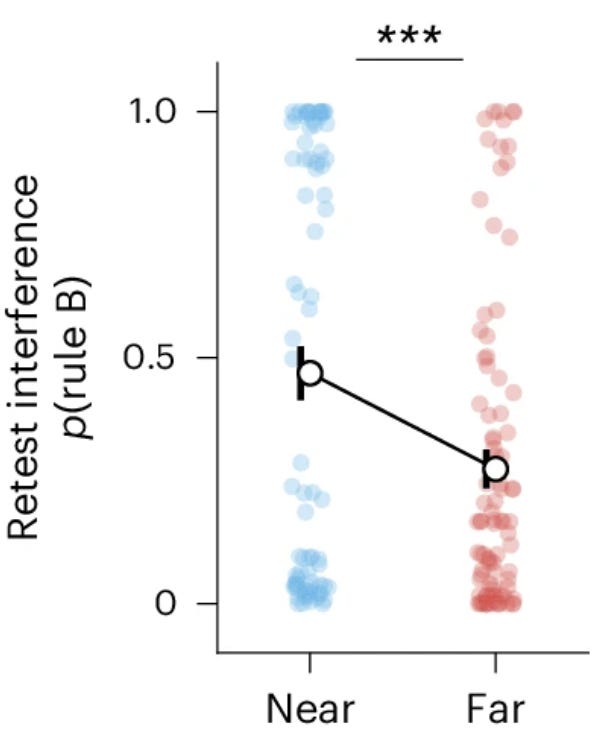

But beneath this averaged regularity lies what appears to be substantial heterogeneity in how people solve the task. This becomes most visible when the rules are similar enough to create genuine ambiguity (the 30-degree shift condition, though patterns may exist in the far condition too). The Near condition participants seem to split into two distinct behavioral profiles:

Some participants (called “lumpers”) showed high transfer but high interference. They immediately benefited from rule A when learning rule B, suggesting they were applying the previous rule to new stimuli. But when retested on task A, they were more likely to apply rule B, apparently overwriting their memory of the original rule.

Other participants (“splitters”) showed the opposite pattern: low transfer but low interference. They treated task B as effectively novel, gaining little immediate advantage from prior learning, and made many more mistakes upon transitioning (higher switching cost). But they maintained rule A better at retest, showing no contamination from the recently learned rule B.

This dissociation extended across multiple behavioral measures beyond the primary transfer and interference metrics. Lumpers appeared to generalize the rule better to held-out stimuli they’d never received feedback on, applying the angular relationship to infer correct responses. But they performed worse on memory for unique stimulus features, specifically the summer locations that had to be memorized rather than inferred from a rule. Splitters showed what looks like the mirror pattern: better memory for unique features, poorer rule-based generalization.

The groups even differed on explicit temporal memory tested at the end of the experiment. Splitters were better at reporting which half of the study they’d first encountered each stimulus in, as if they maintained more distinct representations of the two task contexts.

These differences appear to reflect distinct computational strategies rather than differences in overall ability. Splitters actually outperformed lumpers on some measures (the unique feature memory). Both groups achieved high final accuracy. These look like fundamentally different approaches to solving the same problem, each with complementary strengths and opposite vulnerability profiles.

An important unresolved question is whether these represent stable individual traits or context-dependent strategies. Does someone who lumps in this task lump everywhere? Or do people flexibly shift between strategies based on task structure, recent experience, or environmental statistics? The study design can’t answer this, and it’s a genuinely significant open issue for understanding what these behavioral patterns mean.

Formalizing the Trade-off Through Neural Networks

One of the interesting aspects of this work (and Summerfield’s work more generally) is the use of AI architectures to gain insight into the human mind (and sometimes the brain too).

In this study, the authors used a surprisingly simple neural architecture, a two-layered feedforward network to make some inferences about individual differences in cognitive strategy usage. By manipulating the scale of initial weights, the authors could guide networks toward “rich” (small initial weights leading to structured, low-dimensional representations) or “lazy” (large initial weights leading to high-dimensional, task-agnostic representations) learning regimes.

Networks in the rich regime captured what looks like the lumper behavioral profile: high transfer to Task B, high interference when retested on Task A, strong rule generalization to held-out stimuli, poor unique feature memory, and collapsed representations of the two tasks in neural space (measured via principal angles between task subspaces).

Networks in the lazy regime mirrored what appears to be the splitter pattern on every measure: low transfer, low interference, poor generalization, better unique feature memory, and maintenance of orthogonal representations for the two tasks.

This computational modeling makes the underlying trade-off explicit. Low-dimensional structured representations might enable efficient generalization by extracting shared rules, but precisely because representations are shared across tasks, new learning could overwrite old knowledge. High-dimensional representations might maintain separability between tasks, protecting against interference, but at the potential cost of failing to extract transferable structure.

The value of this modeling approach is that it formalizes what could otherwise remain a vague intuition about competing strategies. The networks make testable predictions: if someone shows high interference, they should also show better generalization within tasks. If they maintain orthogonal task representations, they should show poor transfer but preserved memory.

But we need to be careful about how far we extend the analogy. Having interacted with many humans, I can confirm that none are a two-layered neural networks trained via gradient descent on a single task. How people implement rapid learning likely involves multiple interacting brain systems: prefrontal cortex implementing gating policies that determine when to update versus maintain representations, hippocampus providing rapid contextualization that could separate task episodes, thalamocortical circuits routing information through different processing channels based on task demands. Our behavior, as individuals, probably emerges from how each of our systems interact and are weighted together, something like a mixture of experts where different computational solutions contribute to the final output. Also, the rich and lazy networks are unlikely to describe individual neural systems wholesale, instead, they demonstrate a computational principle that illustrate the trade-off at work (although who knows, maybe each of our brains has a mixture of these principles at work).

The neural network analysis also reveals something interesting about task similarity and strategy visibility. In the Same condition (where both tasks use identical rules), the distinction between lumpers and splitters may not matter much. Everyone can apply the same rule to new stimuli without cost. In the Far condition (180-degree shift), the rules are different enough that most people might naturally treat them as separate tasks, though there may still be some heterogeneity that’s less pronounced. It’s in the Near condition (30-degree shift) where the ambiguity forces different strategies into stark relief, creating the bimodal distribution.

This suggests that algorithmic heterogeneity in how people approach learning might be widespread but often invisible, only becoming apparent when task structure creates the right conditions to pull different strategies apart.

Environmental Contingency and the Absence of a Single Optimal Strategy

The environmental context matters critically for which strategy succeeds. Lumping might dominate when the world has stable structure worth extracting. If rules genuinely repeat across contexts, you learn faster by recognizing and applying patterns. The cost of occasional interference could be outweighed by the acceleration in learning new tasks that share structure with old ones.

Splitting might win when rules change frequently or when maintaining distinct memories is crucial. If what you learned before is often misleading rather than helpful, protecting each memory from contamination becomes more valuable than speed of transfer. The cost of slow learning could be justified by the accuracy of what you retain.

There may be no single “correct” strategy. The optimal approach likely depends on the statistics of the environment you’re navigating. A world with high regularity and stable rules rewards generalization. A world with frequent rule changes or high context-specificity rewards separation and protection of distinct memories. There is also the possibility that luck plays a role; what you just encountered may predispose you to lump or split depending on how successful you just were.

This raises an interesting possibility about cognitive diversity. Rather than representing noise around some ideal cognitive architecture, the coexistence of lumpers and splitters might reflect adaptation to environmental variability. A population containing both strategies might outperform a homogeneous population, with pattern-extractors thriving in stable domains and detail-preservers succeeding in volatile ones. Different algorithmic profiles suited to different ecological niches.

This interpretation is speculative, but it suggests we might want to think about individual differences in learning strategies as positions on a trade-off curve that evolution or development has explored.

Relevance for Understanding Disorders

This level of behavioral dissection seems important for understanding psychiatric heterogeneity. If we only measured final task accuracy, lumpers and splitters would be indistinguishable. Standard neuropsychological testing focused on whether performance is intact or impaired would miss this entirely. It’s only by examining the pattern of performance across multiple measures (transfer, interference, generalization, unique feature memory, temporal context) that the different strategies become visible.

This has potentially important implications for how we study psychiatric conditions. Consider what we know about cognitive function in schizophrenia. Working memory deficits are consistently documented. Counterfactual reasoning appears impaired. Context processing shows abnormalities. But we typically describe these as simple deficits, performance falling below some normative threshold.

What if some of this heterogeneity reflects people navigating trade-offs differently, perhaps forced toward one extreme by underlying capacity constraints? Someone with severe working memory limitations might be pushed toward splitting strategies, unable to maintain the flexible representations needed for successful generalization. Alternatively, they might be pushed toward excessive lumping, overgeneralizing because they can’t maintain distinct context representations. Or the computational machinery for balancing these strategies might be disrupted in ways that don’t map onto the healthy spectrum at all.

Without tasks that can behaviorally dissect these possibilities, separating transfer from interference, generalization from discrimination, rule application from memory for specifics, we can’t distinguish these accounts. We end up with general statements about “cognitive deficits” when we should be asking about specific algorithmic profiles and how they interact with task demands.

The implications here concern the level of analysis we need. Detailed statistics of behavior, comparison to normative computational models when available, careful dissection of performance patterns across conditions that pull different strategies apart.

And we should remember the limitations of the analogy: people aren’t one big neural network. Multiple brain systems (prefrontal gating, hippocampal context coding, thalamic routing) likely contribute to how we handle sequential learning. These computational principles might illuminate trade-offs and formalize what behavioral patterns we should look for, but the implementation almost certainly involves coordination across systems rather than a single learning mechanism. The behavioral signature we observe is likely the weighted output of this complex architecture.

Emphasis on Methodological Insight

The methodological contribution here may be as important as the empirical findings. Averaged behavior can look normal, even optimal, while masking fundamentally different computational strategies operating beneath the surface. Standard cognitive assessments can show intact performance while missing the algorithmic heterogeneity that might matter for understanding vulnerability, predicting treatment response, or matching individuals to environments.

The sequential learning paradigm with separate measures of transfer and interference provides one example of how to pull these strategies apart. The neural network modeling provides a formal framework for understanding what different patterns of performance might mean. The combination suggests a path forward for computational psychiatry that goes beyond asking whether performance is impaired.

The next generation of this work might ask: Which specific algorithmic trade-offs are being navigated differently? What behavioral signatures reveal underlying strategy? How do these computational profiles interact with environmental demands? When does being a lumper become maladaptive, and when does being a splitter limit learning?

The demonstration that careful behavioral dissection can reveal hidden heterogeneity in how people learn suggests we might be missing similar structure in other domains by averaging too quickly and testing too coarsely.

Synthesis: What We Learn About Learning

The capacity to abstract while preserving details represents a fundamental computational challenge for any learning system, biological or artificial. The tension appears intrinsic to intelligence itself.

What optimal looks like depends entirely on environmental structure. Stable worlds with repeating patterns reward those who extract and apply rules quickly. Volatile worlds where yesterday’s pattern misleads today reward those who maintain distinct memories and avoid overgeneralization. The problem itself changes based on context, making any single solution inadequate.

This has profound implications for how we think about cognitive diversity. Individual differences in learning strategies might represent different positions on a fundamental trade-off curve, possibly shaped by recent experience, current capacity constraints, or the statistics of environments people have navigated. Cognitive styles might reflect computational strategies. Apparent deficits might be extreme positions on trade-offs that have no objectively correct answer.

The biological implementation is almost certainly a weighted mixture of multiple brain systems coordinating to produce the behavior we observe. Disruption might affect these systems differently, push trade-offs toward extremes, or create computational patterns that don’t exist in healthy populations at all.

The brain’s solution to the quiet war between abstraction and detail appears to be “it depends on the brain and it depends on the world.” Understanding both dependencies seems necessary for making sense of how learning works, why it sometimes fails, and what interventions might actually help.

Work like this only matters if it reaches people wondering about these questions. If you found value here, consider sharing it with your community. Subscribe if you want to see where this type of thinking and analysis goes.

This got me reading about DQN and the Atari experiment and 'their' approach to generalization... the rabbit hole gets sooo much deeper with the idea of how its structural learning is conceptually similar to ours (?) if that makes sense... I'm not a neuro bro but the parallels between AI and neural systems is wild to "see"...

This is very thought provoking- but I’m not sure if I lumped or split my way to those thoughts.

Huge implications for therapy - of which I’ve had a lot - and the lenses that are applied to clients currently. . .