Precision Psychiatry for Depression: What genetics and neuroimaging revealed in 2025

Two 2025 studies showed better outcomes when treatment was guided by biomarkers

A 48-year-old woman has been on three different antidepressants over two years, each one helping a bit but never enough to get her through a full day at work without feeling depleted and disconnected. One day she mentions that her son was recently diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and her psychiatrist decides to add lithium to her regimen despite being uncertain about the choice given her lack of clear bipolar traits, telling her honestly that her son’s diagnosis tipped the balance toward trying it. Six weeks later she experiences what she describes as a lifting, not just of depressive symptoms but of something deeper that had been weighing on her for years, and she’s enjoying her work in ways she hadn’t thought possible anymore. At the eight week appointment she describes reconnecting with friends she’d been avoiding and planning a vacation with her husband for the first time in years. Was this ever just depression, both of them wonder, or was the family history revealing something about her biology that the symptom pattern alone had obscured?

A 34-year-old man presents with depression but also chronic difficulties with focus, organization, and completing tasks at work, describing himself as feeling scattered and forgetful in ways that seem beyond typical depressive concentration problems. His presentation led his previous provider to diagnose him with ADHD and start him on stimulants. Unfortunately, this made him more anxious and jittery without touching the underlying depression or improving his ability to finish projects. His current psychiatrist finds herself uncertain whether she’s looking at depression with prominent cognitive symptoms, ADHD with comorbid depression, or something that doesn’t fit cleanly into either category. More importantly, she is not sure whether she should try a different antidepressant, return to stimulants at a lower dose, or consider that the cognitive symptoms might represent a distinct subtype requiring a completely different treatment approach that neither of them has fully considered yet.

Every psychiatrist has been confronted with these types of uncertainty in diagnosis and management. The DSM forces us to choose diagnostic categories based on which symptoms we emphasize, which then guide treatment options. As I have written previously, psychiatry is at a disadvantage compared to the rest of medicine which has X-rays, EKGs and various blood tests to help reduce uncertainty. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a way to identify people who would respond to lithium augmentation so we can save them lost years of trial and error? If something told us that cognitive augmentation in a depressed patient would end up targeting the core machinery of negative thoughts because the person is presumably stuck in a self-reinforcing narrative that drains cognitive resources and also manifests as depression symptoms, wouldn’t we want to start them on this medication right away?

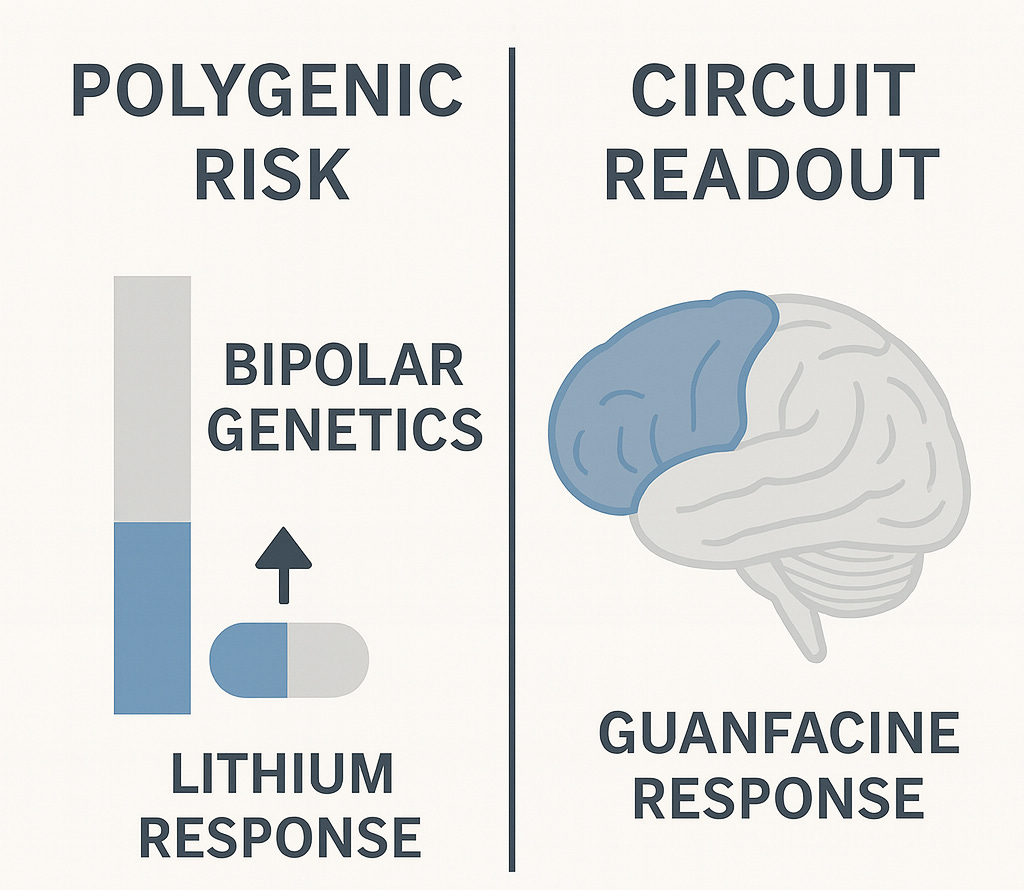

Two papers published in 2025 suggest we can now do exactly this, one using genetics to identify who will respond to lithium augmentation and one using neuroimaging to identify who has the specific circuit dysfunction that predicts response to cognitive enhancement strategies. Both demonstrate that objective biomarkers can guide treatment selection in depression by revealing biologically distinct subtypes hidden beneath the single diagnostic label of “major depressive disorder,” and both show dramatic improvements in outcomes when patients are matched to mechanistically appropriate treatments rather than their symptom presentation alone.

The challenge for precision psychiatry has always been that identifying subtypes only generates clinical value if those subtypes actually predict treatment response, since psychiatric diagnosis earns its keep by changing what we do rather than by reorganizing how we think about phenomenology. We can parse depression into as many biotypes as we wish using genetics or neuroimaging or cognitive testing, but if they all respond to the same antidepressants with the same probability, then it is not clear what the point is. This is why these two studies I am highlighting represent something more significant than biomarker identification.

Lithium response points to subtypes we’re missing

The JAMA Psychiatry paper from Kraft and colleagues in September analyzed 193 patients with major depressive disorder who hadn’t responded adequately to at least one antidepressant and then received lithium augmentation for at least 4 weeks, calculating polygenic risk scores (PRS) for schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder to see whether genetic profiles predicted response. The patients came from 13 psychiatric hospitals in the Berlin area, most of them on SSRIs or SNRIs when lithium was added, with overall response rates around 47% and remission rates around 32% before accounting for genetic differences.

The findings show that patients with high bipolar genetics responded to lithium at much higher rates than those with low bipolar genetics: 56% versus 35%, which is a substantial difference if you’re the patient waiting to find out whether your fourth medication trial will work. The effect isn’t huge in absolute terms (bipolar genetics explain about 5% of who responds) but it’s real and consistent enough that the statistics hold up under scrutiny. More on that later…

The major depression polygenic risk score showed the opposite pattern: patients with higher depression genetics were less likely to respond to lithium, while schizophrenia genetics showed no relationship to lithium response at all. So lithium responders have bipolar genetics and lack depression genetics, which is about as clear a signal as you could ask for that these aren’t just “treatment-resistant depression” patients who happen to respond to lithium but rather patients with bipolar biology who never met full diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder.

The paper points to this interpretation explicitly, noting that previous studies found higher lithium response in patients with family history of bipolar disorder and in those who later converted to bipolar depression, suggesting that many lithium responders represent what they call “subthreshold bipolar depression”; individuals carrying bipolar genetics but lacking the classic manic episodes that would trigger a bipolar diagnosis. Maybe they had brief hypomanic periods that went unnoticed, maybe their mood elevation was attenuated by other genetic or environmental factors, or maybe they’re early in a trajectory that would eventually include more obvious bipolar features, but regardless of the specific clinical history, their genetic profile and treatment response reveal an underlying biology that phenomenology-based diagnosis missed entirely. Perhaps we should be looking for the algorithmic correlates instead of symptoms or genes alone.

This gets at something important about precision psychiatry: genetics here isn’t replacing behavior but rather pointing us toward patterns we should be looking for more carefully in the first place. Someone with high bipolar genetics who responds to lithium may have subtle mood variability, energy shifts, or sleep pattern changes that distinguish them from someone with “pure major depression”, but we’re not phenotyping carefully enough to catch these differences during a standard evaluation. Our diagnostic thresholds ask whether you had elevated mood for 4 days or 7 days, whether it was impairing enough, whether anyone noticed, but those are arbitrary cutoffs that may miss a deeper behavioral phenotype that guides treatment. Perhaps more careful behavioral measurements with direct brain readouts can help fill the gap here?

Circuit imaging suggests a cognitive subtype

The Nature Mental Health paper by Hack and colleagues did exactly that; building on a subgroup analysis from a large randomized clinical trial for depression. That work analyzed over 1000 patients and found that roughly a third of people with major depression diagnosis cluster together based on prominent impairments in executive function and response inhibition (using actual tasks), along with reduced activation in prefrontal cognitive control circuits in the response inhibition task. Importantly, this cognitive biotype+ showed significantly lower remission rates with standard antidepressants compared to other depressed patients suggesting they represent a distinct subgroup that needs different treatment approaches.

The 2025 paper extends this work by testing whether using the identified circuit readout as a treatment selection method would improve outcomes. They prospectively selected seventeen patients who met criteria for the cognitive biotype based on both task performance (impaired performance on cognitive control tasks) and neuroimaging (reduced activation in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and dorsal anterior cingulate during response inhibition). They then treated them with guanfacine, an alpha-2A receptor agonist that enhances prefrontal function and is already used off-label for ADHD.

The results were striking: 76.5% response rate and 64.7% remission rate after eight weeks, compared to the roughly 39% remission this group typically shows with standard antidepressants and the 33% baseline rate across all depression patients. Guanfacine also improved the circuit dysfunction itself, with increased activation in the dorsal anterior cingulate and strengthened connectivity with prefrontal cortex, and these circuit changes correlated with clinical improvement, suggesting the drug was engaging its intended target and that normalizing this circuit led to symptom relief.

The obvious limitation is that this was seventeen patients without a placebo control, so we need larger randomized controlled trials to know whether these effects are robust. But if the findings hold up under proper controlled conditions, we’re looking at something like a depression EKG for a specific subtype: objective tests (behavioral and circuit-based) that tell you which patients with depressive symptoms have the prefrontal dysfunction that predicts poor response to standard antidepressants but potentially good response to circuit-targeted treatments like guanfacine. That would change how we approach diagnostic and treatment decisions for patients who present with depression plus prominent cognitive symptoms, moving from educated guessing to biomarker-guided selection.

Considerations for future drug development

The broader lesson here for pharmaceutical companies is that enrichment strategies based on biomarkers might be the way to go, which shouldn’t be surprising given oncology’s experience over the past two decades but somehow remains controversial in psychiatry. When you select patients whose biology matches your drug’s mechanism, effect sizes appear to improve dramatically, which could mean you can run smaller trials with clearer answers about whether a mechanism works in the population where it’s supposed to work.

This has potential implications for how we might want to design clinical trials in psychiatry. The standard approach of enrolling several hundred patients who meet DSM criteria for major depression and measuring small differences on rating scales produces marginal effects, possibly because we’re testing drugs in populations where maybe only 20-30% have the relevant biological dysfunction. If instead we enrich for the specific circuit dysfunction or genetic profile that a mechanism targets, we might need far fewer patients to see whether a drug engages the right biology and produces meaningful clinical improvement.

The economics could shift substantially if we can answer mechanism questions with 50 well-selected patients instead of 400 heterogeneous ones, particularly for repurposed medications where the molecule is off patent but the biomarker-stratified indication would be new. Guanfacine and lithium have been generic for years, but guanfacine for circuit-defined cognitive depression and lithium for genetically-defined bipolar spectrum disorder within major depression would be novel indications based on precision selection that might justify development investment even without compound exclusivity.

These studies also raise the possibility that some portion of psychiatric drug development failures over the past few decades might reflect testing potentially good mechanisms in the wrong populations rather than mechanisms that fundamentally don’t work. Alpha-2A agonism looks mediocre in heterogeneous depression samples but produces dramatic effects when you select for prefrontal cognitive circuit dysfunction - at least in one small study. The mechanism might have been fine all along, just applied to the wrong population. How many other failed programs might reflect the same problem? We don’t know, but it’s worth asking.

The practical barrier is developing biomarker assays that are feasible outside academic centers and economically viable within healthcare systems, but that seems like a surmountable problem if the effect sizes justify the investment. Polygenic risk scores are already becoming commodity tests, and circuit-based assessments could potentially be streamlined substantially from Stanford’s research protocol if there’s clinical demand. The question is whether drug developers will start building trials around precision enrichment strategies or keep running heterogeneous studies hoping for small average effects that satisfy regulators but don’t necessarily transform patient outcomes.

Precision Psychiatry for Depression

We’re at an interesting moment where the technology to do precision psychiatry in depression is maturing and producing better outcomes, but the infrastructure and incentives to make it routine practice don’t exist yet. Polygenic risk scores cost a few hundred dollars and return results in weeks, circuit-based fMRI assessments are available at major academic centers, and both approaches appear to identify patients who will respond dramatically better to specific treatments than to standard antidepressants, but neither test is something you can order on a Tuesday afternoon when you’re trying to decide whether to add lithium or switch to a different SSRI.

The question over the next five to ten years is whether psychiatry follows a trajectory where biomarker-guided treatment selection goes from research curiosity to standard practice once the evidence became overwhelming and pharmaceutical companies started building development programs around it, or whether precision approaches remain boutique confined to academic centers because the practical barriers prove too difficult to overcome. Or maybe the effect sizes, while impressive in small studies, don’t replicate broadly enough to justify the added complexity and cost. This is a similar problem to one I recently wrote about here.

What’s different now compared to previous waves of enthusiasm about biomarkers in psychiatry is that these studies connect directly to treatment decisions rather than just offering biological insights that don’t change what clinicians do. Knowing someone has high bipolar genetics changes whether you try lithium, knowing someone has prefrontal circuit dysfunction changes whether you try guanfacine, and both decisions could spare patients years of ineffective medication trials if the findings hold up in larger samples. That’s a different value proposition than precision proposals that reorganize how we think about disorders without reorganizing which treatments we choose.

The proof of concept is here, the technology is feasible, and the clinical need is obvious to anyone who’s watched patients cycle through multiple failed antidepressant trials. What happens next depends on whether the stakeholders who would need to make this routine practice see enough value to justify the investment in infrastructure, whether regulators create pathways that make biomarker-stratified indications economically viable, and whether these initial findings replicate in the larger controlled studies that would be needed to establish this as standard care. We’ll know a lot more in five years about whether precision psychiatry in depression becomes more of a reality or remains within the purview of academic medicine.

If you found this useful, consider subscribing. I cover developments in computational and precision psychiatry, including how emerging biomarkers can shape clinical care and drug development.

The polygenic risk score approach is pretty smart for catching subthreshold bipolar cases that don't fit the DSM boxes. If someone's genetics scream bipolar but they never hit the full mania checklist, you're basically guessing blind on lithium unless you look at family history. Running PRS before trial and error could probably cut down those multi-year journeys through failed antidepressants.

I like guanfacine as a longterm heart health replacement for Vyvanse - for myself; but consider that depression leaves lasting degenerative cognitive symptoms (whether natural or pharmaK treated iatrogenic side FX , no?) - stimulants can be helpful to balance that out 😉

Theories of depression polarization and categories are always interesting! Thanks! ☺️